Understanding Neurodiverse Relationships

About the Author

For over 20 years, Grace Myhill has worked with neurodiverse couples and has pioneered specialized training for therapists in how to work with neurodiverse couples more effectively. Here Grace discusses some of the key areas she addresses with neurodiverse couples and what she has learned over the years working in this field.

On differing perspectives…

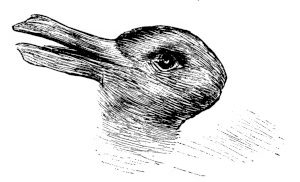

When working with any neurodiverse couple in therapy, one of the key elements is helping each partner understand the concept of different yet equally valid perspectives. Just as when viewing this classic illustration one person might see a duck and one might see a rabbit and both would be accurate, partners may see the same situation or conversation in an entirely different way and both views would be valid. It is important for partners to approach their relationship always knowing that there is not one owner of reality. You each have a brain that has unique filters: your psychology, your gender, your ethnicity, your experiences, your family history, but also your neurology. It is important not to make assumptions that you know what the other person is thinking or that the other person knows something.

Very often an Autistic person may not realize there are multiple perspectives. They have grown up thinking that their perspective is the only perspective and believing their way of thinking is the only way. And sometimes once they get a formal diagnosis or they realize they are on the spectrum through self-discovery, it is the first time they understand that maybe other people don’t think the same way they do. And if there is a neurotypical partner, they may have also assumed their Autistic partner understands situations or interprets language the same way as others in their life. But actually their partner may interpret things quite differently from a neurotypical person, such as taking words more literally and not recognizing what is intended by particular body language or tone of voice. Both Autistic and neurotypical partners may need to release the judgement they have held about what one person knows or doesn’t know and recognize the validity of the other partner’s perspective.

Refraining from making assumptions goes for the therapist too. In that role, you are always trying to understand both people, interpret for each through their own neurological lens, but also checking it out with them to make sure that you are getting it right yourself. That allows you to really help the partners see and have compassion for how the other person’s brain works.

On relationship evolution…

When I first meet with a neurodiverse couple, I want to understand the larger picture of their relationship journey. As a therapist, I start to ask questions: When were things different? Was your courtship like this, or was your courtship different? And usually they say, “Well, things were better back then.” So the question becomes: How were they different? One turning point I often see in neurodiverse relationships is moving from dating to cohabitation. This is a significant step for any relationship, but for neurodiverse partners, there may be unique challenges. The change from seeing each other every few days to seeing each other constantly creates a demand on an Autistic partner they may not have anticipated. The loss of down-time and the increased expectation for communication may be too much of a cognitive load. But in protecting downtime, the other partner may feel slighted and think they are not the priority. Recognizing the needs of each partner and finding a balance that serves those needs becomes paramount.

While hearing stories of the couple’s history, I listen for Autistic traits and interpret through a neurological lens to uncover where the neurodiversity between the partners might be at the root of their issue. Say, for instance, one partner complains their partner never goes to their kid’s football games. The other partner may give reasons that might be interpreted as excuses or defensiveness. As the therapist or relationship coach, it is critical to go deeper into those stories, listen to the explanations, and really get at what is going on. For a situation like this, I might ask: Could it be sensory sensitivities? Are there other situations where you avoid large crowds? Are there executive functioning issues making it difficult to plan to attend or leave work? Sometimes people don’t even realize the underlying issues at play. Uncovering these root issues helps to show when certain requests are unrealistic for a partner to fulfill, and the partners can begin to build understanding and compassion.

On communication…

One of the other important differences between partners can be communication styles. One partner might give a lengthy explanation about something and the other person can’t process it all at once. They may need it broken down into smaller pieces. On the other hand, a person may speak in too few sentences, especially one word answers, without asking connecting questions, like how the person felt or what their experience was like. This can be interpreted as being rude or abrupt, that the person doesn’t care, and it doesn’t provide the feeling of connection the other partner needs. Another common issue is partners interrupting each other and not allowing the other to finish their thoughts before jumping in.

Partners can bridge the divide when they become aware of their own communication styles and the style of their partner, gain a greater understanding of what their partner needs, and talk through strategies to bring them closer to balance. This could be a code for when you need the person to pause their story or when you need the person to say more. To avoid interruptions, partners can use a “talking stick” with the rule that whoever is holding it is the only one speaking until it is passed over. Concrete tools like these can help partners recognize and give each other what each needs in order for the communication to be effective, efficient, and connecting.

So much of strong communication is listening and trying to stay with what your partner is asking of you. Often neurotypical partners are seeking for an empathic response, not necessarily problem-solving response. For many Autistic individuals, that’s incredibly illogical. Why would you even communicate about something that you don’t want to solve? But for many neurotypical partners, every communication is a bid for connection for them in their language. And if they don’t hear something back, then they feel like their partner is not there, and they feel alone.

On what makes a neurodiverse relationship work…

The most successful neurodiverse relationships are the ones where the needs and expectations are well matched. Sometimes when both partners are on the spectrum, there may be a deeper understanding if they share the same interests and have similar needs. When there is a neurotypical partner and an Autistic partner, there can be a recognition of their neurological differences and a genuine willingness to accommodate each other. They may also have different needs they can coordinate, such as one partner’s need for social time with a group of friends, which can be scheduled to coincide with the other partner’s need for solitude.

In any neurodiverse relationship, sometimes a person might not meet their partner’s needs and expectations, not because they are oblivious or trying to hurt their partner, but because it is something they simply cannot do. It’s about reaching a balance that is good enough for both people. But you need an understanding of neurological differences, the building of compassion for each other, and the communications skills to get there.

Stay Current

Subscribe for AANE weekly emails, monthly news, updates, and more!