Autistic Burnout to Autism Discovery

Language Note: Over the decades, many different terms have been used to discuss autism. AANE is shifting to identity-first language and the term “Autistic” to describe our community, but we continue to respect each individual’s choice of language to describe their own neurotype. We believe that sharing a wide variety of stories provides invaluable insight into the diverse perspectives and experiences of our community.

Graduate school wasn’t hard – it was a nightmare. I struggled at the start and then continued to underperform. Then, I declined further. Little by little. Placed on academic probation. Continued to decline. After about five years, I finally began to approach the final hurdle: publishing a lead-author manuscript. My PhD advisor, not satisfied in my progress, purposely failed me for the semester. I had few friends. School left time for few other interests and not much free time. But I was back on academic probation again. My PhD advisor then decided to move to a different university.

Trying to avoid starting over or moving to a different university myself, I took everything I had left and shifted into high gear. To secure a training grant to fund myself to keep going, I enrolled in a second graduate program and shifted my dissertation’s focus. The plan was I’d finish after a year.

About another two years passed, and I eventually did publish my lead-author paper. A couple months into writing the dissertation, I still had nothing done. My time spent “working” was mostly sitting on the couch doing nothing, frozen in panic and indecision. This struggle persisted for months.

No longer supported by any grant or university funding and just living off of some savings, I finally submitted my dissertation about five months later. I defended my thesis, and without a job or much of a plan, I moved across the country, away from everything else.

Life After Graduate School

Everyone had asked me, “What are you going to do after you graduate? Will you do postdoc? Study a new research field? Pursue a career in industry?” My answer? “Nah, I’d like to retire…” They would laugh. But the feeling was genuine. I had nothing left in the tank. Completely burned out. Why, after a seven-year collection of disasters and breakdowns, would I sign up to do MORE of this? Hard pass. Zero interest.

Through some luck, I moved into a house with an old friend, and his two roommates. I finally got my wish: no work, just rest. No job. No stress. For four months.

But despite this, my burnout state never improved. I grew distant from my friend and other roommates. I eventually got a job, starting out at just 10 hours a week. This left me without the energy to be social or to talk about anything. Too tired to fake it. Pretty quickly I stopped trying all together. Didn’t leave the house. Hardly left my bedroom. Had groceries or whatever I needed delivered. Eventually, I moved into my own place by myself. I was done with daily social interactions. I needed to be completely left alone.

But, despite no major distractions, no roommate stress and even having my own office space, I still struggled to get anything done at my new job. Fumbled through forced work conversations. No focus. Hardly any brain output. I felt like my brain’s tires were just spinning in circles, stuck in mud. Doing little else for myself but just trying to work. And all this effort to get nowhere.

My lack of productivity did not go unnoticed by my boss. My boss, the reason I got this job in the first place, was a former co-worker and friend of mine. She was coming from a place of concern and wanting to solve whatever problem I was clearly having. But I didn’t want to face reality. With my failures being laid out in front of me as facts, I saw this as a personal attack.

I had a couple of very uncomfortable confrontations with her like this until eventually I admitted that I had at least some sort of problem focusing, and that I would seek help for that. After a couple of weeks and a visit to a psychiatrist, I was diagnosed with ADHD.

A New Diagnosis

Following that news, I was truly, very excited! My work productivity picked up. I could sit still for hours at a time and happily do all the tasks I wanted to do. Things weren’t perfect, of course, but every week, as my medication dose increased slightly, I got a little clearer view of my true self and potential. Over the course of a month, I felt as if I had been slowly emerging from a mental fog, leaving behind a several-year era of brain haze.

I can tell you the exact day I made it all the way out. Feeling like my old self again, having fully emerged from the chaos and noise, the truth about myself was looking back right at me. It was as if I was staring at my own reflection in a pond which had always been cloudy and was now still and clear. I could finally see my true self. I had seen it in others before but never in myself. I had Asperger’s Syndrome!

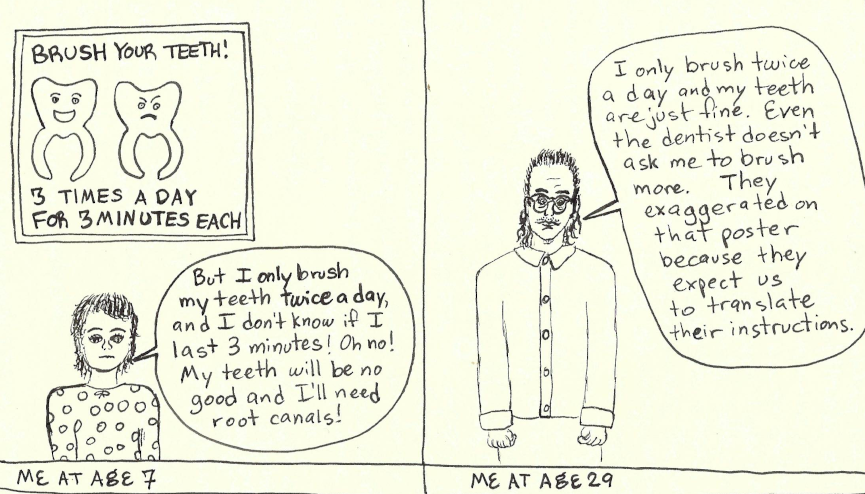

I already knew about autism. I just hadn’t known about myself. I hadn’t just burned out from graduate school. Years and years of fooling myself and others, years of pretending to be neurotypical, had weighed on me until I collapsed. I was suffering from autistic burnout. It all made sense now!

I wish I could say I initially responded to this autism revelation with the same excitement I had with my new ADHD diagnosis. I spent a long time ruminating, and so much effort belaboring over the past. I was angry with myself and the world, trying to grapple with this impossible regret that had I somehow known this sooner, I could have avoided so many struggles I had suffered. I could have started therapy decades earlier. I could have found more understanding of myself and made better decisions.

The Road to Recovery

The turning point was when I began to appreciate the good news about what this autism discovery actually was. I had always felt different than everyone else and never understood why. But now I finally knew what this difference was. As a firm believer in “knowledge is power,” I started to wonder: how can I use this new knowledge about myself to my benefit?

I started to take inventory of my strengths and weaknesses. I started to strategize how I can make the most of my autistic “superpowers” and use them to help myself improve the things about me that weren’t so “super.” Then, the key was baby steps — very small but steady attempts to work on myself and work with myself every day. Not with the intention of making my burnout “better”… Rather, with the intention to work towards a version of me I’d be most proud of.

It hasn’t been too long now since I made this change. It’s too soon to tell if my burnout is gone or “better,” but I know I feel better. I’m hopeful I’ll feel a little better tomorrow, too.

Stay Current

Subscribe for AANE weekly emails, monthly news, updates, and more!